In a previous post I told you how Howard Street got it's name. As a matter of fact, many of the streets in Evanston are named after local land developers or people of note. But only one person has each of his three names - first, middle, and last, assigned to Evanston streets. Who was that person? Chancellor Livingston Jenks. What can we find out about Mr. Jenks and why are three streets named after him? Let's see what we can "dig up".

Chancellor Livingston Jenks was born January 29, 1828 in Warren, Bradford County, Pennsylvania, the fourth of seventeen(!!!) children born to Livingston Jenks (1789-1863) and Sally, nee Buffington (1796-1866) - and that does not count their four adopted children! Of the seventeen children, nine lived to adulthood. They are: Cynthia (1816-1874), Sarah (1822-????), Nancy (1824-1911), Chancellor (1828-1903), Charles (1830-1893), Oliver (1831-1880), William (1834-1914), Olive (1836-1887) and Abigail (1838-1911).

Chancellor was a direct descendant on both sides of men who fought in the Revolutionary War. On his father's side he was descended from Captain Joseph Jenkes from the Army of Independence, and on his mother's side from Preserved Buffington, a member of the Rhode Island Regiment.

When Chancellor was a boy the family moved from Pennsylvania to Illinois, buying a farm in Deer Park in La Salle County. From a young age, Chancellor knew that farming was not for him, and in 1851 he came to Chicago to study law under Calvin DeWolfe. While he was practicing law, he was also buying up real estate, agreeing with Mark Twain who said, "Buy land, they're not making it anymore".

On May 6, 1855 at the First Methodist Church of Chicago he married Miss Pamella Maria Hoisington (1831-1890) of Montreal, Canada. Pamella was the daughter of Jasper Albert Hoisington (1801-1895) and Pamella, nee Manning (1799-1881). Chancellor and Pamella were blessed with six children: Albert (1856-1890), Charles Lawrence (1858-1898), Edwin (1861-????), Chancellor Livingston Jr. (1863-1937), Laura Belle (1865-1874), and Livingston Jenks (1868-1918).

As Chancellor Jenks' time and money allowed, he kept adding to his real estate holdings. In 1868, in connection with Charles E. Brown and others, he acquired a large tract of land in what is now the Sixth Ward of Evanston, and laid out the sub-division known as North Evanston. He was also one of the founders of Glencoe and, in addition to his holdings in Chicago, invested largely in Englewood, Hyde Park and elsewhere. Mr. Jenks' real estate interests having become so extensive as to demand his entire attention, he was compelled, with great reluctance, to give up the practice of the law not long before the Great Chicago Fire. That catastrophe almost ruined Jenks financially, and just as he was regaining his footing the second great fire of 1874 happened, again caused him extensive losses. Since the land itself was still there, Jenks was able over time to recoup his losses and ended up in better shape over the long run.

In politics Chancellor Livingston Jenks was always a staunch Republican, and before the Civil War, he and his father were active abolitionists, and their farm in La Salle County was a station of the so-called "Underground Railroad," established to aid runaway slaves in escaping to Canada.

Interestingly, Chancellor Jenks is best remembered today not for his real estate holdings, or his efforts to improve Evanston schools. He is best remembered in connection with his efforts on behalf of a runaway slave girl.

In August of 1860, when he was in downtown Chicago, Jenks saw a runaway slave girl at Clark and Van Buren Streets named Eliza Grayson struggling in the grasp of her master, Stephen F. Knuckles, and Jack Newsom, a commissioner under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 declared that all runaway slaves upon capture were to be returned to their masters. Abolitionists nicknamed it the "Bloodhound Law" for the dogs that were used to track down runaway slaves. Seeing the young girl struggling with the two men, Jenks promptly rushed to the assistance of the girl with the result that soon the entire group were rolling over each other in the gutter. When police officers arrived on the scene, they were all taken into custody. The runaway slave alone was imprisoned; the others being well known and responsible, were released on their own recognizance. Planning to get the better of the slaveowners, Jenks immediately swore out a warrant charging the slave with disorderly conduct. Jenks' mentor and fellow abolitionist, (now Justice) Calvin De Wolf issued the writ at 10:00 at night. George Anderson, Deputy Sheriff (who was in on the "conspiracy") served the warrant at once, and took the girl from the police station with the apparent purpose of producing her before the magistrate. On the street he was surrounded by a howling mob of several hundred persons, and, when the crowd was dispersed, the prisoner was nowhere to be found. Before morning Eliza Grayson was on her way to Canada and freedom. Back in Chicago, the Federal Grand Jury which was then in session, promptly indicted Chancellor Jenks, Calvin De Wolf and George Anderson on the charge of violating the Fugitive Slave Law. The affair coming to the knowledge of President Buchanan, he made the somewhat natural mistake of supposing "Chancellor" Jenks to be a judge of one of the State courts on the chancery side. Indignant at this instance of open violation of a cherished (by Buchanan) United States statute, he telegraphed the United States Attorney at Chicago as follows: "Prosecute Chancellor Jenks to the full extent of the law. For a private citizen to be engaged in such nefarious practices as he is charged with is bad enough; but a high officer of the Court, should be severely dealt with. (Signed) James Buchanan, President." Shortly afterward Abraham Lincoln was elected President, the Civil War broke out, and the political complexion of the Federal officers at Chicago changed. As if by magic, the indictment against Chancellor Jenks and his two "co-conspirators" was dropped.

Pamella Hoisington Jenks died April 5, 1890 in San Diego, California while visiting their son Chancellor Jr. Here is her death notice from the Chicago Daily Tribune of April 7, 1890:

After his wife's death Chancellor Jenks spent the summers living with his son Chancellor Jr. at 1217 Ridge in Evanston, and the winters in San Diego, California where the elder Jenks had real estate investments.

Chancellor Livingston Jenks died in San Francisco, California on January 10, 1903 while visiting his son Livingston Jenks. Here is his obituary from the Chicago Daily Tribune of January 11, 1903:

and his Death Notice from the Tribune of January 16, 1903:

Chancellor Jenks was laid to rest beside his beloved Pamella in Rosehill Cemetery in Chicago:

After finding out that Chancellor Livingston Jenks laid out the subdivision known as North Evanston, it is not surprising that streets are named after him. Supposedly only Jenks Street is named after him; Chancellor and Livingston streets are named after his sons. But there they are all in a row: Chancellor, Livingston, and Jenks Streets in North Evanston.

Chancellor was a direct descendant on both sides of men who fought in the Revolutionary War. On his father's side he was descended from Captain Joseph Jenkes from the Army of Independence, and on his mother's side from Preserved Buffington, a member of the Rhode Island Regiment.

When Chancellor was a boy the family moved from Pennsylvania to Illinois, buying a farm in Deer Park in La Salle County. From a young age, Chancellor knew that farming was not for him, and in 1851 he came to Chicago to study law under Calvin DeWolfe. While he was practicing law, he was also buying up real estate, agreeing with Mark Twain who said, "Buy land, they're not making it anymore".

On May 6, 1855 at the First Methodist Church of Chicago he married Miss Pamella Maria Hoisington (1831-1890) of Montreal, Canada. Pamella was the daughter of Jasper Albert Hoisington (1801-1895) and Pamella, nee Manning (1799-1881). Chancellor and Pamella were blessed with six children: Albert (1856-1890), Charles Lawrence (1858-1898), Edwin (1861-????), Chancellor Livingston Jr. (1863-1937), Laura Belle (1865-1874), and Livingston Jenks (1868-1918).

As Chancellor Jenks' time and money allowed, he kept adding to his real estate holdings. In 1868, in connection with Charles E. Brown and others, he acquired a large tract of land in what is now the Sixth Ward of Evanston, and laid out the sub-division known as North Evanston. He was also one of the founders of Glencoe and, in addition to his holdings in Chicago, invested largely in Englewood, Hyde Park and elsewhere. Mr. Jenks' real estate interests having become so extensive as to demand his entire attention, he was compelled, with great reluctance, to give up the practice of the law not long before the Great Chicago Fire. That catastrophe almost ruined Jenks financially, and just as he was regaining his footing the second great fire of 1874 happened, again caused him extensive losses. Since the land itself was still there, Jenks was able over time to recoup his losses and ended up in better shape over the long run.

In politics Chancellor Livingston Jenks was always a staunch Republican, and before the Civil War, he and his father were active abolitionists, and their farm in La Salle County was a station of the so-called "Underground Railroad," established to aid runaway slaves in escaping to Canada.

Interestingly, Chancellor Jenks is best remembered today not for his real estate holdings, or his efforts to improve Evanston schools. He is best remembered in connection with his efforts on behalf of a runaway slave girl.

In August of 1860, when he was in downtown Chicago, Jenks saw a runaway slave girl at Clark and Van Buren Streets named Eliza Grayson struggling in the grasp of her master, Stephen F. Knuckles, and Jack Newsom, a commissioner under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 declared that all runaway slaves upon capture were to be returned to their masters. Abolitionists nicknamed it the "Bloodhound Law" for the dogs that were used to track down runaway slaves. Seeing the young girl struggling with the two men, Jenks promptly rushed to the assistance of the girl with the result that soon the entire group were rolling over each other in the gutter. When police officers arrived on the scene, they were all taken into custody. The runaway slave alone was imprisoned; the others being well known and responsible, were released on their own recognizance. Planning to get the better of the slaveowners, Jenks immediately swore out a warrant charging the slave with disorderly conduct. Jenks' mentor and fellow abolitionist, (now Justice) Calvin De Wolf issued the writ at 10:00 at night. George Anderson, Deputy Sheriff (who was in on the "conspiracy") served the warrant at once, and took the girl from the police station with the apparent purpose of producing her before the magistrate. On the street he was surrounded by a howling mob of several hundred persons, and, when the crowd was dispersed, the prisoner was nowhere to be found. Before morning Eliza Grayson was on her way to Canada and freedom. Back in Chicago, the Federal Grand Jury which was then in session, promptly indicted Chancellor Jenks, Calvin De Wolf and George Anderson on the charge of violating the Fugitive Slave Law. The affair coming to the knowledge of President Buchanan, he made the somewhat natural mistake of supposing "Chancellor" Jenks to be a judge of one of the State courts on the chancery side. Indignant at this instance of open violation of a cherished (by Buchanan) United States statute, he telegraphed the United States Attorney at Chicago as follows: "Prosecute Chancellor Jenks to the full extent of the law. For a private citizen to be engaged in such nefarious practices as he is charged with is bad enough; but a high officer of the Court, should be severely dealt with. (Signed) James Buchanan, President." Shortly afterward Abraham Lincoln was elected President, the Civil War broke out, and the political complexion of the Federal officers at Chicago changed. As if by magic, the indictment against Chancellor Jenks and his two "co-conspirators" was dropped.

Pamella Hoisington Jenks died April 5, 1890 in San Diego, California while visiting their son Chancellor Jr. Here is her death notice from the Chicago Daily Tribune of April 7, 1890:

After his wife's death Chancellor Jenks spent the summers living with his son Chancellor Jr. at 1217 Ridge in Evanston, and the winters in San Diego, California where the elder Jenks had real estate investments.

|

| 1217 Ridge, Evanston |

Chancellor Livingston Jenks died in San Francisco, California on January 10, 1903 while visiting his son Livingston Jenks. Here is his obituary from the Chicago Daily Tribune of January 11, 1903:

and his Death Notice from the Tribune of January 16, 1903:

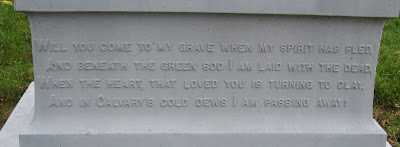

Chancellor Jenks was laid to rest beside his beloved Pamella in Rosehill Cemetery in Chicago:

After finding out that Chancellor Livingston Jenks laid out the subdivision known as North Evanston, it is not surprising that streets are named after him. Supposedly only Jenks Street is named after him; Chancellor and Livingston streets are named after his sons. But there they are all in a row: Chancellor, Livingston, and Jenks Streets in North Evanston.

Chancellor Livingston Jenks - a man willing to fight for his principals, and the namesake of three Evanston streets - may he rest in peace.

.JPG)

.JPG)